An early find revealed the origins of the temple

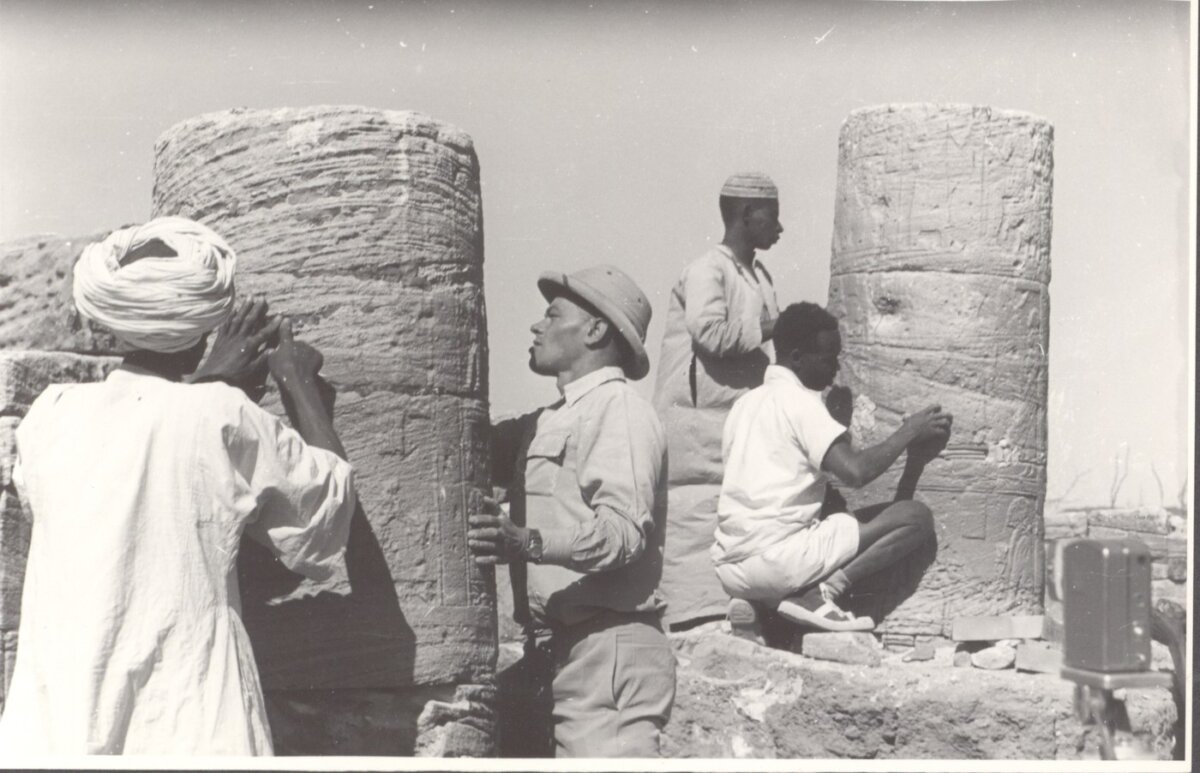

The objects and archival documents from the collection on display in the Humboldt Laboratory provide an insight into the start of research on site. Fritz Hintze’s archaeological field diary documents the excavation and its main results, while Ursula Hintze vividly describes the surrounding events in her personal diary. Her notes show: On the day of the discovery, the mood was euphoric. ‘The diary bears witness to the team’s enthusiasm about this early success of the excavation. It’s a wonderful, important moment,’ says Cornelia Kleinitz. On this ‘big day’, Fritz Hintze found a sandstone block with two so-called royal cartouches, oval, engraved lines enclosing the names of rulers – in this case King Arnekhamani (around 220 BC) – in the lintel of an ancient temple. ‘This solved the mystery of the chronological classification of the temple and its builder,’ explains the archaeologist.

Other relief parts refer to the temple’s patron, the lion-headed god Apedemak. The Apedemak or lion temple of Musawwarat, whose reconstruction was financed by the GDR, is therefore the oldest known building dedicated to this local god and an important part of an ensemble of monumental buildings in the Musawwarat es-Sufra valley. They date from the time of the Kingdom of Kush (8th century BCE to 4th century CE) in northern Sudan. The sacred site has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2011.

History of science from a women’s perspective

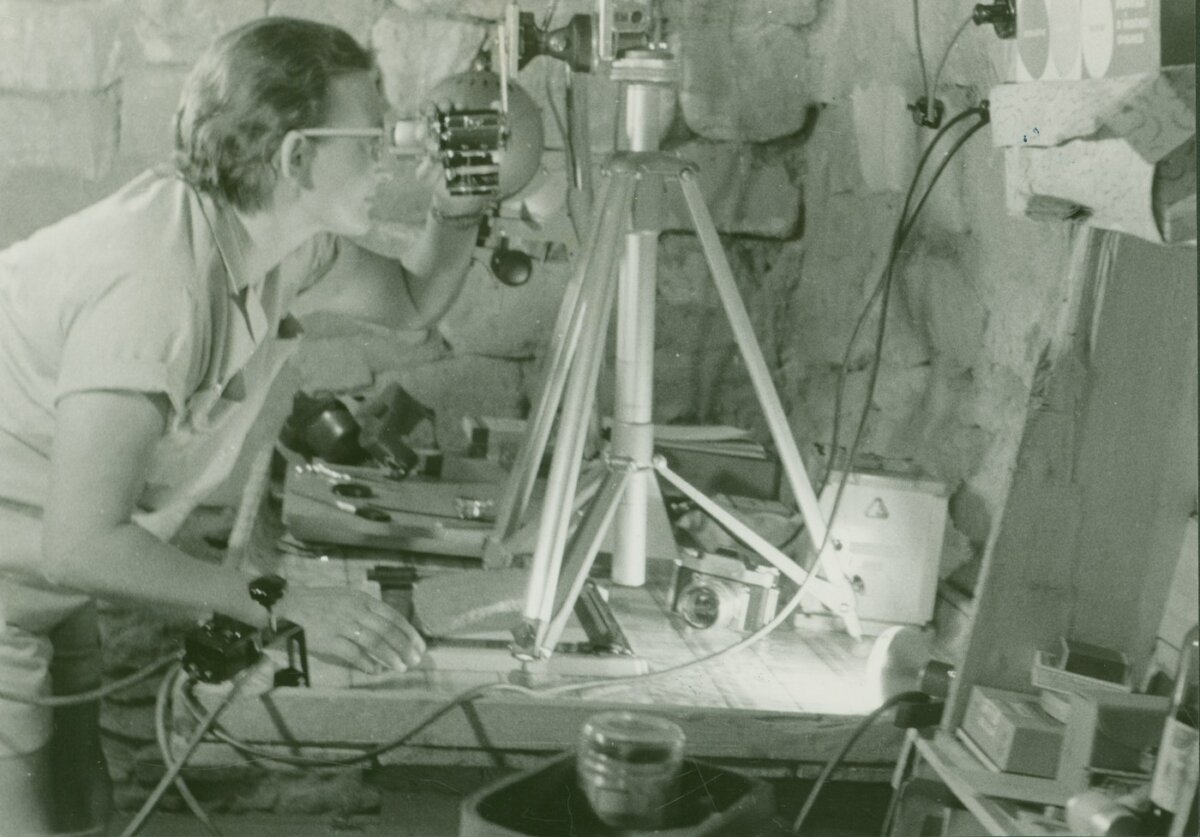

The archival documents selected for the Humboldt Lab’s inaugural exhibition include diaries and photographs by Ursula Hintze. Ursula Hintze developed her photos on site herself – under extreme climatic conditions such as heat and drought. ‘She played a key role in the organisation and documentation of this excavation,’ emphasises Cornelia Kleinitz. The Africanist filmed, photographed, wrote and quickly learnt the local language in order to communicate with the partners.

The example of Mr and Mrs Hintze shows that the merit of women as scientists or co-scientists is often underestimated, says Gorch Pieken. The Humboldt Labor aims to shed light on the role of women researchers – and to critically scrutinise the history of science. ‘The collections consist of many omissions and powerful representations. Certain things are emphasised and marked as important. These are often the scientific achievements of men.’ One could already speak of an ‘academic patriarchy’ that has by no means been overcome. ‘We can also see this, for example, in the fact that the proportion of women among German professors is only 25 per cent,’ says the Head Curator. A fictitious special stamp was created for the exhibition to highlight Ursula Hintze’s role and to honour her in retrospect. It shows the Africanist at work with a hat, sunglasses and her camera in her hand.