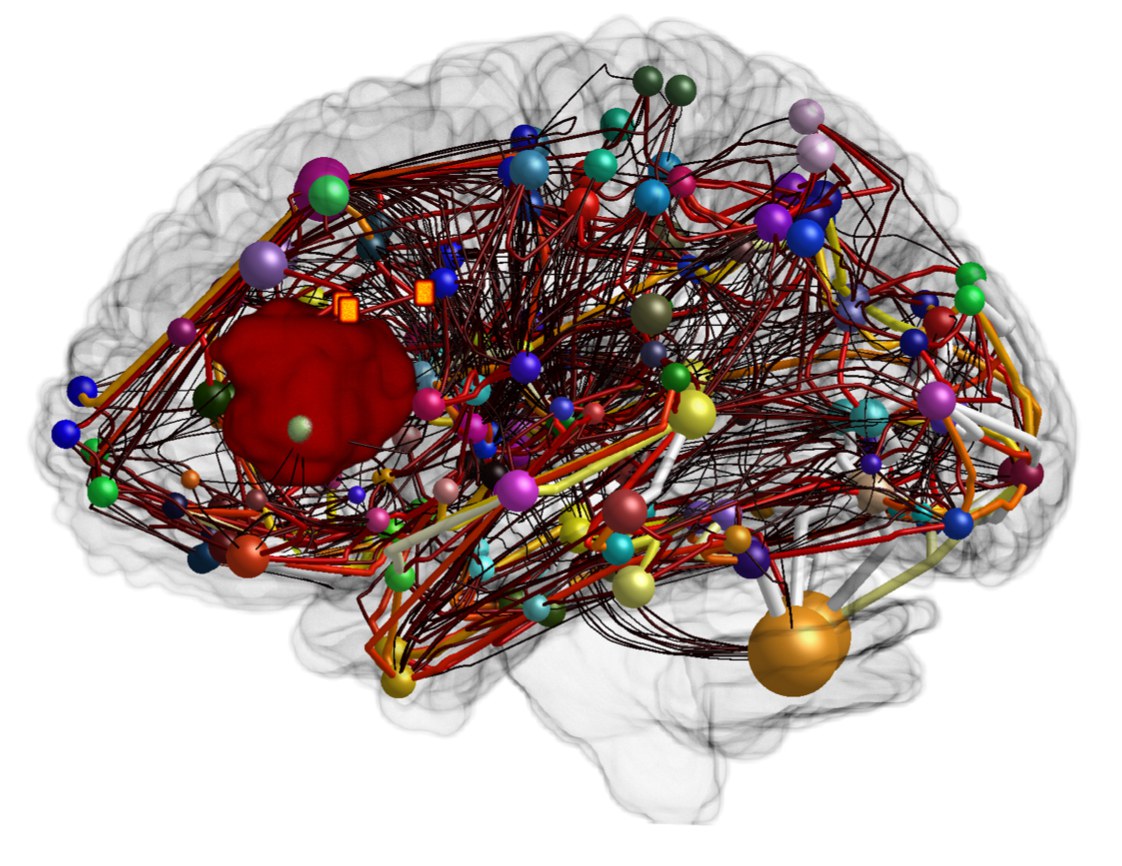

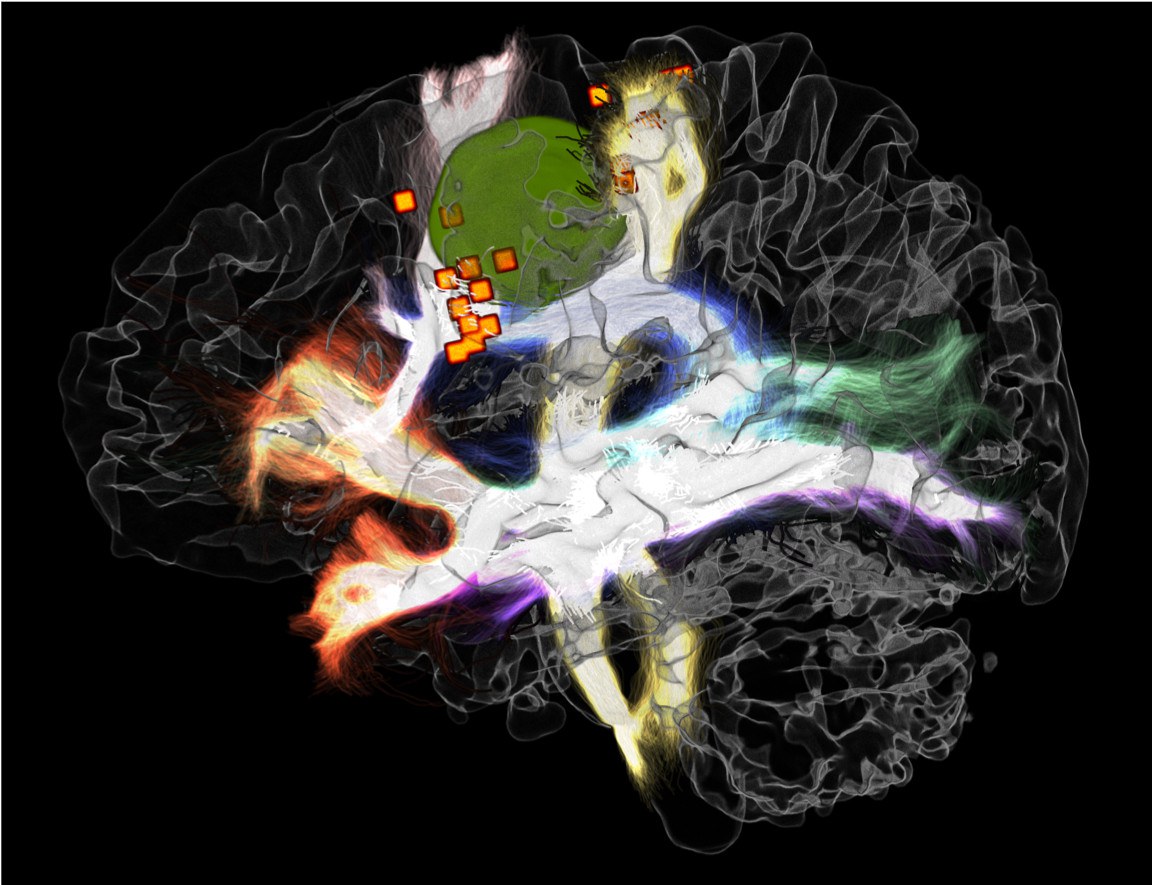

At a research station in the Humboldt Lab, the ‘Adaptive Digital Twin’ project of the Cluster of Excellence ‘Matters of Activity’ and Charité Berlin will take a look inside the human brain. 3D models of this complex organ will be shown as holographic representations. In clinical practice, such visualisations support the preparation of operations, for example.

Holographic projections are considered an obligatory fixture of science fiction series. However, they have now arrived in reality – as holographic displays in the Humboldt Lab will show. Two such ‘Looking Glasses’ can be used to inspect 3D models of the human brain, virtual twins of our most complex organ.

Such visualisations are not only appealing for aesthetic reasons, they also serve medical purposes. ‘This is something we work with every day,’ reports Lucius Fekonja, research associate at the Department of Neurosurgery at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the Cluster of Excellence ’MATTERS OF ACTIVITY. IMAGE SPACE MATERIAL’ (MoA). He is leading the development of the ‘Adaptive Digital Twin’, an ‘adaptable, digital twin’ of the human brain. This project is based at the Image Guidance Lab (IGL), an interdisciplinary working group of the neurosurgery clinic at Charité and the MoA Cluster of Excellence at Humboldt University in Berlin, headed by PD Dr Thomas Picht.